That Battle is Over, Girl: Alice Schoenberg

LUMA QUARTERLY | ISSUE 019, VOLUME FIVE | WINTER 2020

read online here

I was speaking to my friend, Bones, over the phone and expressed that I wanted to make her a playlist, mostly out of guilt for not replying to her text messages for the past month. She returned the sentiment and we decided on the theme of light frost green. I compiled a collection of songs that made me think of being depressed and laying on the mossy forest floor,1while Bones’ playlist seemed to be inspired by a fairy emoji.2 While listening to her playlist, I heard Norwegian singer-songwriter Jenny Hval’s 2015 song “That Battle is Over” for the first time.

Swaying drums link up to organs and synths that create an expanding field for Hval’s sharp-witted lyrics. She moves between deep murmurs to high crests, polysyllabic runs to drawn out notes. Hval’s gentle quiet purr raises up to a high peak singing out, “You say I’m free now?”.3 Her voice settles into a sultry gentle sway saying “You say I'm free now, that battle is over and feminism is over & socialism's over. Yeah, I say I can consume what I want now”.4 Confronting insidious forms of repression, Hval points not just to society as a manifestation of her oppression as a woman, but also to the systemic structures surrounding her. Her simultaneously adolescent and potent voice questions if capitalist consumption really represents any form of systematic liberation. The song itself became an echo for me for Alice Schoenberg’s performance and video work, in particular what her superwoman character represents.

I first met Schoenberg at the Alberta University of the Arts together where we both graduated in April 2019. Despite having only had one class together in our final semester, I became familiar with the superwoman character that had become central in Schoenberg’s artistic practice. Screen captures and photographs of Schoenberg with overdrawn red lips and a light blue skin-tight suit filled her studio as she developed the character. A campy and hilarious manifestation of a superwoman, the persona is tall and her red platform Pleaser boots elevate Schoenberg to a sexual level, strutting in both her performances and videos. Schoenberg describes the superwoman as “this homegrown vigilante woke up one day and thought I'm gonna change the world, though no one asked her to…she was like: I am gonna keep going, I think, I think it'll help, and I think that if I go on Facebook and I walk with 800 versions of me, it'll help the people that I am overshadowing.”5Through enacting laborious yet futile tasks, she questions liberation and power of both marginalized and non-marginalized bodies, while challenging the commodification of activist action and social justice.

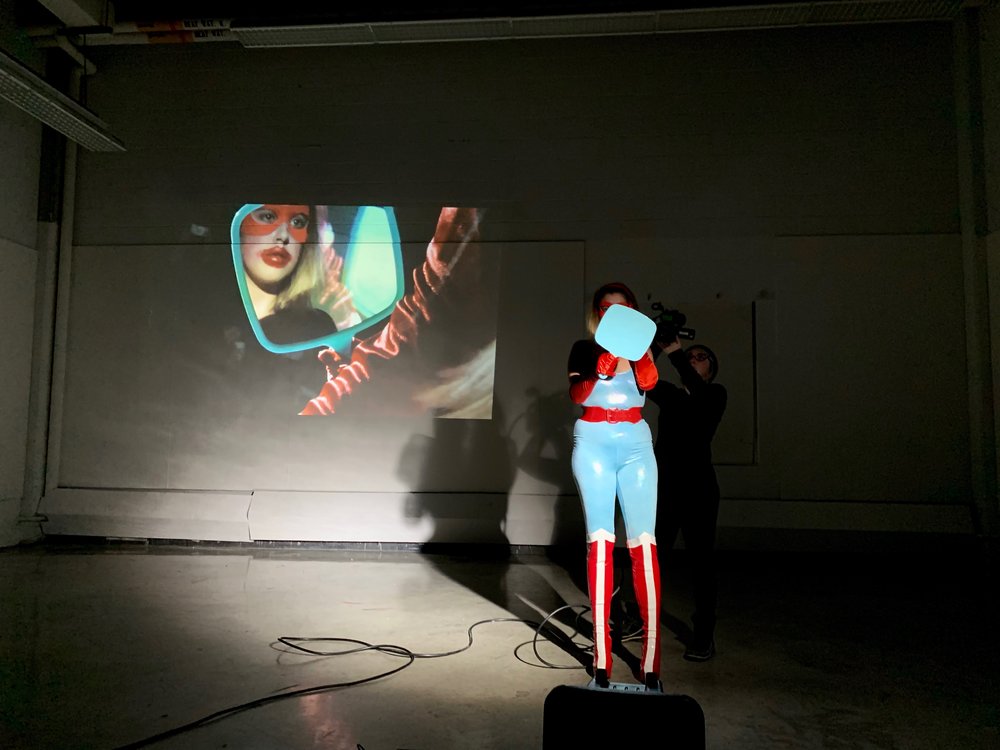

Her superwoman character appears in THIS IS A PROTEST (2018), performed in the dark and highlighted by a strong incandescent spotlight, and a projection on the back wall. The superwoman stands in the spotlight, with a light blue mirror in her hands, and she begins to take an exploratory look at her body through the mirror. The gesture recalls feminist art critique and implies the potential empowerment of ‘getting to know and reclaim her body’. Behind her a handheld video camera sends live footage of the reflection in the mirror to a projector behind the superwoman. Over the speakers, a computerized voice repeats “This is a protest” in unnerving drone audio. As the superwoman continues her action, continually consumed through the camera behind her, the computerized voice starts to glitch and fail. The voice then goes silent as the superwoman turns to face the camera. The computerized voice begins stating “This is an image”. In the mirror held in her hand, we can see her smiling.

This shift from the superwoman engaging with the mirror to facing the camera drove home Schoenberg’s critical engagement with feminist movements. The inclusion of the camera demonstrates how easily these exploratory actions are consumed by a capitalist gaze. Schoenberg describes the camera as “this intrusive thing that even [the superwoman] who is not the person to be writing this ideal feminist image is also not sure of this image, but there's still this camera that is picking up and projecting widely this fractured image”.6The superwoman is even willing to endorse this gaze and use it for her own promotion. By turning to face the camera, her exploratory gaze becomes a performative one, meant to be consumed by the camera. Her gestures become less meaningful than the image produced out of them and the supposed empowering action is now flattened into the fractured image.

During the performance Ladder(Later)al Movement (2019), my gaze wanders to the top of a yellow ladder, where the superwoman balances perilously on the steps. The precarious tension of watching her walk up a ladder in spanking red platform boots is both nerve wrenching and amusing and yet it seems cruel to chuckle in the dark space as she struggles. The ladder is illuminated with the light from two large projectors, the rest of the darkened room recedes into the back of our minds, no longer as interesting the bright projections, full of colourful looping found footage of the 2015 Women’s March in Washington, DC. We wait in the dark, not moving. When the superwoman makes her wobbly ascent to the top of the eight-foot ladder, it seems impressive. Her tall boots make a potential fall seem much more imposing, dangerous, and exaggerated. She sits at the top and watches the sped-up footage of bodies filling the streets until yellow text begins to scroll down the wall. The superwoman begins reading out the text, a monologue that begins to describe in both abstract and literal ways privilege, capitalism, and government-mandated regulation through police presence surrounding the Women’s March.

The superwoman, now resting easily on the top of the ladder, forgets her climb. Now, she ponders how the ladder arrived under her. “I must say, I’m not sure how I got up here in the first place, I guess just the right place at the right time.” Schoenberg said. “I think this ladder was likely here before I was, in fact I’m almost sure of it. But I don’t really remember climbing up here in the first place. Maybe it grew up from under me. Or maybe I happened to drop down and land on it.” The suspension of her memory parallels the forgetful memory of white privilege in contemporary activist movements. She holds a the microphone and; her voice is finally heard, thus, in the superwoman’s perspective, there is no need to be uncomfortable. She finishes her monologue with a singsongy statement: “She’s a lady, woah woah woah she’s a lady, talking about that big lady, and the lady is commodified so as to exert control over her movement and procure profit through enforced lack”.7

It’s a blunt but humorous comment coming from someone sitting on top of ladder in a campy superhero costume. The superwoman begins her descent, humming “She’s a Lady” by Tom Jones on her descent. Back on the industrial concrete floor, she picks up a pink blank sheet of paper and paces while holding it over her head until she seemingly gets bored, and exits the room.

Repression exists in the failures of memory and the whisper of “things are better now”. As Schoenberg describes it: “There's this element of social forgetting but, a lot more is this individual forgetting, forgetting that you were at one point the thing that you now disdain, forgetting that you probably still are that thing.”8In Later(Ladder)Al Movement, the superwoman is continuously clumsy, as is her recollection of her past. Her lack of memory highlights the layers of privilege that exist within contemporary feminist movements, and the forms of oppressions (such as racism and transphobia) that remain ingrained in these movements. Through forgetting her climb as a white woman, the superwoman no longer is interested in the climbs of others. Her voice drawls: “[…] the snakes which run along the ground […] encourage me to stay up here while biting at other people’s ankles.” 9 Success in capitalism, success through colonial structures encourage the superwoman to stay on her ladder. The calm of being above the audience is seductive for her. In her exit, she realizes that her hunger for change is superficial, and easily remedied.

In Systemic Activism (by and for this body only) (2019) Schoenberg positions the Woman’s March10as a case study for the failures of contemporary feminist movements. A massive, full wall projection in dark room, the video again features the superwoman, this time contending with the pink pussy hat; a knit symbol of the Women’s March meant to imitate cat ears and imply that all women have pussies. Schoenberg expands on Systemic Activism (by and for this body only) as a new step in the superwoman persona, stating she was interested in “leaning into villainy a little bit more, before this the superwoman was a little bit more like ‘I don't really know what I'm doing’ and this was more like: no she's lazy, grumpy, she's whining about getting up and doing anything; [I was] letting her be a more indulgent person, and leaning into her worst qualities, and maybe cradling my own image a little bit. Saying oh god I just have to be the asshole, because part of you is this asshole.”11

In employing scrolling text and found footage of the Women’s March, the superwoman demonstrates the failures of this march, pointing to the consumption of activist image and failed integration of capitalism into the contemporary feminist movement. She squats behind text that reveals her true nature: “I am sold for profit for political advancement for economic gain”. She occupies different spaces of privilege and emptiness from the bare backdrop of a green screen to the iconic Sims computer game, used to simulate a suburban utopia and digital lives. She acts as an exhausted figure of a failed revolution, now occupied with the ulterior motives to be consumed and to act out activist movements.

Throughout the video Schoenberg argues that a government-mandated act of activism is in fact an act of sedation of those in greater positions of privilege instead of an act of social or political change. Real change isn’t being accomplished and yet the performed and displayed asking of change is appealing and encouraged by governmental bodies. This is already predicted in Later(Ladder)al Movement, when the superwoman states: “There’s no threat here, just a whole lot of white people with pink signs, hungry for change and leaving this day rather full.” 12

The perceived achievement of equality is an insidious form of repression itself. It manifests in the statement, “Well I sure don’t feel oppressed”. In creating a lack of challenging action through the sedation of the most privileged in an activist movement, we achieve nothing. Those who stand on the top of a ladder do not need to dismantle it, nor invite company. The stillness that arises out of privilege and lack of memory in activist movements becomes those same movements frailty. In “That Battle is Over”, Hval sings of “It's fearful out here on the calmest seas, we who grew up singing Merry Christmas! War is over.”13Within these lyrics, Hval references the song “Happy Xmas! (War is Over)”14 by John Lennon and The Yoko Plastic Ono Band, a song full of optimism and heavily engaged anti-war activism, which stands in direct contrast with the calmest seas, a metaphor for the stagnation of action that arises out of a lack of critical engagement with privilege within activist movements. What Schoenberg and Hval demonstrate is that the longer that systems of oppression convince activist movements that it is possible to co-exist, the more impotent those activist actions become.

Within a new Albertan United Conservative Party cutting funds to the public sector, including education and health care, the exhaustion within my community is evident. Repeated acts of protest and activism go seemingly unheard, and underfunded non-profit organizations need to overwork their small staffs to keep their organizations afloat. A constant question I have in my head as of late: How do we thrive in this, not just survive it? Schoenberg doesn’t provide us with a solution. The superwoman is not our role model. But in this Schoenberg and Hval point to our weaknesses, providing a much needed critical and humorous perspectives on the spaces that still need to be filled and restructured. Schoenberg states: “It’s not to make allowances [for people who have made social missteps] but the room for learning and being self-critical for the sake of the people who have had to be teaching for so long”.15